Pro-democracy Legislative Councillor Tanya Chan (center right, black shirt) breaks up a fight at a protest outside the old Legislative Council building on June 23, 2010. I took this photo while in Hong Kong on a summer exchange program which placed me with the Civic Party for a few weeks. Chan lost her seat on the Legislative Council on Sunday’s election thanks to nominating strategy and a flawed vote allocation system.

In Hong Kong, you win by losing.

In yesterday’s Hong Kong Legislative Council, the pro-democracy Civic Party won the most votes in Hong Kong Island and New Territories West, but managed to win only one seat in each district as the rival pro-Beijing DAB got two each. Another large pro-democracy party, the Democratic Party had enough votes to win a seat in New Territories West, but won zero. How is this possible?

The answer is in the voting system. Much like how structural problems in the voting system gave George W. Bush a victory in the infamous 2000 Presidential election, the Civic Party lost out on two extra seats thanks to a voting and apportionment system flaw. While no voting system is perfect, as proven mathematically by Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem, the selection of the Hare quota and highest-remainders is especially helpful to pro-Beijing parties like the DAB.

Hong Kong voters went to the polls on September 9th to vote for their 70-member Legislative Council, a body stacked with “functional constituencies” that give pro-Beijing parties a guaranteed majority. However, 35 seats are elected in geographical constituencies ranging from 5 to 9 seats that use closed-list proportional representation. Specifically, Hong Kong uses the Largest Remainder or Hare quota.

From Wikipedia:

The largest remainder method requires the numbers of votes for each party to be divided by a quota representing the number of votes required for a seat […] The result for each party will usually consist of an integer part plus a fractional remainder. Each party is first allocated a number of seats equal to their integer. This will generally leave some seats unallocated: the parties are then ranked on the basis of the fractional remainders, and the parties with the largest remainders are each allocated one additional seat until all the seats have been allocated.

There’s a reason most countries that use proportional representation have switched away from the Hare quota to a highest-averages method like D’Hondt or Sainte-Lague: the Hare quota is extremely vulnerable to strategic voting (配票 pui piu), and strategic nominating. If your party is trying to win two seats in a district, and polling shows that you have enough support, you have two choices.

1. Run one list. The Civic Party chose this strategy. This virtually guarantees the first person on your list will win a seat, but whether your ticketmate wins depends on how high your remainder is–and you’ll need a high remainder. If you are running in a crowded constituency, all of the remaining seats might be gone before it’s your turn again. You do not need to allocate votes to different lists, you simply need to pile as many votes as possible on one list.

2. Run two lists. The Democratic Party and the DAB chose this strategy. You need fewer total votes to win two seats. Ideally, your two lists would win highest remainder seats. However, if you have overestimated your support or misallocate your votes, both your lists might lose, leaving you with no seats. This requires machine-like precision to avoid total 失敗 (sat baai…failure).

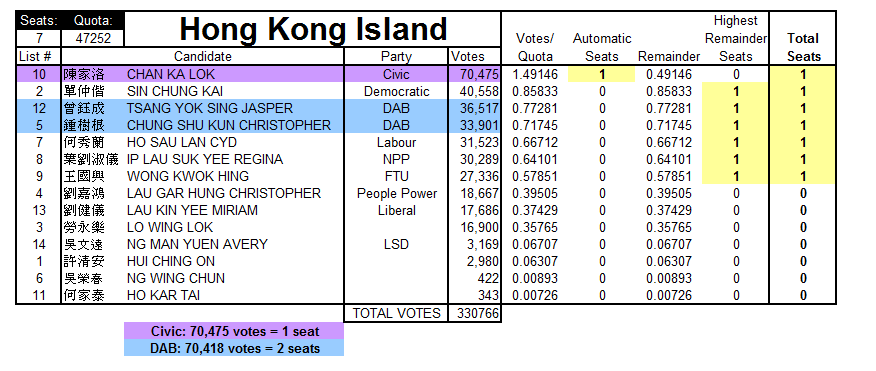

Let’s see how Option A turned out for the Civic Party. Results are below:

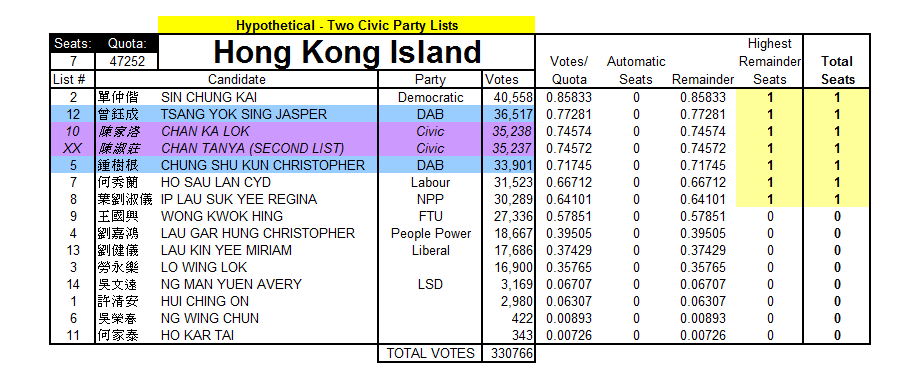

The Civic Party won the most votes, highlighted in purple. The DAB, however, ran two lists: and even though the Civic Party beat the DAB by 57 votes, the DAB won two seats! Had the Civic Party split their candidates into two lists, and split their votes perfectly evenly, they would have won two seats, as shown below:

Hypothetically, splitting into two lists would have given the Civic Party two seats: but the real world does not necessarily work like this.

This strategy is not foolproof. Running one list was less risky because it guaranteed Chan Ka-lok’s election even if they didn’t have enough support for a 2nd seat. Had the Civic Party overestimated their support by 8,000 or 9,000 votes, both lists would have lost. Balancing the votes evenly would have been an even more difficult challenge for the Civic Party, because they intentionally gave newcomer Chan Ka-lok the first spot, placing incumbent legislator Tanya Chan second. Splitting votes between a well-known quantity and a political newcomer would have been a very risky proposition.

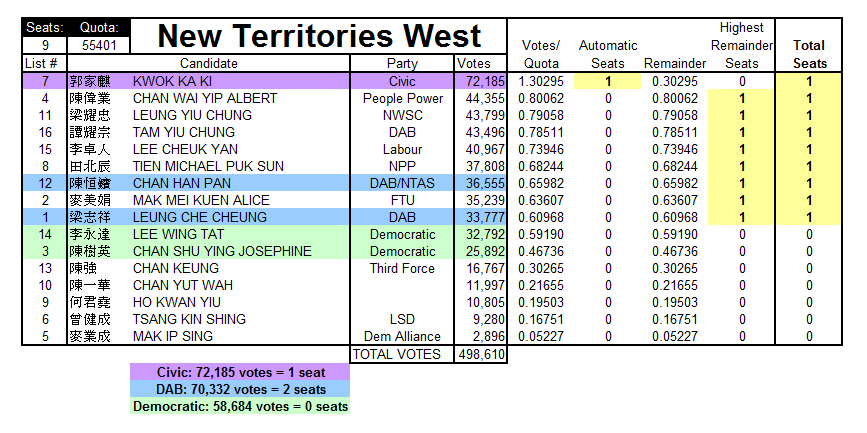

The one-list strategy also gave the Civic Party only one seat in New Territories West. But it’s more complicated than that….results below:

In New Territories West, the Civic Party placed popular legislator Audrey Eu second on their list behind former LegCo member Kwok Ka-ki. They again finished first in votes, ahead of the DAB, but received only 1 seat where the DAB received two. Total disaster struck the Democratic Party, which ran two lists and saw both just miss the threshold, resulting in no seats: the worst possible outcome.

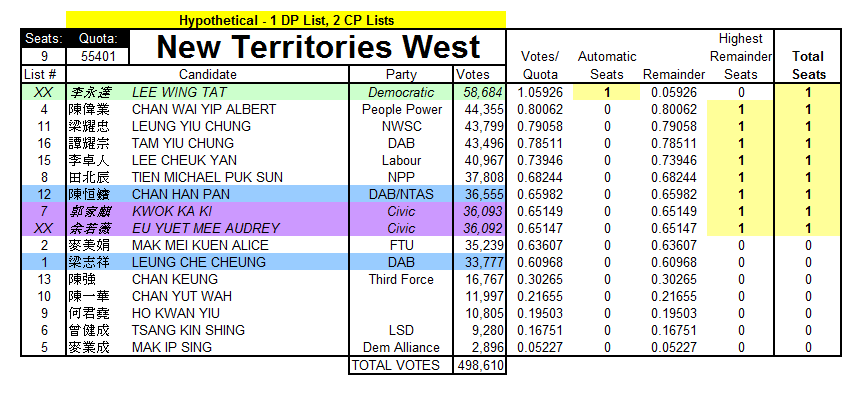

Had the Civic Party ran two lists, and the Democratic Party one list, this would have been the result:

On the surface, this scenario gives the Civic Party two seats, but this would have been nearly impossible, given how thin the margin between them and the FTU would have been. A mis-allocation of just a few hundred votes would have lost one or both seats! Moreover, the Democratic Party ran two lists: had both the Democratic Party and Civic Party run two lists, aiing for four seats, it’s quite likely that they would have ended up with zero seats between them even as their votes outnumbered the DAB.

In the end, the Democratic Party chose a risky strategy to win extra seats, and was punished. The Civic Party chose a safer strategy, hoping for four seats in these two constituencies, but comfortably elected two instead. The DAB chose the same strategy as the Democratic Party, but won more votes and split them effectively between two tickets for 4 seats. Noted, again that the Civic Party won more votes than the DAB in both constituencies.

These are not strategic blunders by the pan-Democratic camp. The selection of the Hare quota (which, again, has been abandoned in general worldwide) was a deliberate choice by Beijing after the 1997 handover. The DAB is widely known to have the organizing force of the mainland Chinese government behind it, and as such is much better able to execute the machine-like maneuvers these strategies require.

The 1991 and 1995 Legislative Council elections for the geographical constituencies were held using American-style first past the post, single member districts, like our US House of Representatives. Both elections resulted in overwhelming majorities within the geographical seats for the United Democrats of Hong Kong. It is well-known that first-past-the-post encourages the formation of two monolithic parties (Duverger’s Law), apparent in the tight grip that the two-party system has had on the United States for two nearly uninterrupted centuries. After the handover, the current system was put in place, which encourages parties to splinter and rewards tight organization.

American liberals have long lamented infighting in the Democratic Party, and sometimes gripe that conservatives are naturally more likely to fall in line. While this isn’t always true, nobody falls in line like the pro-Beijing DAB supporters. Who else could be more obedient than sympathizers to a one-party Communist China? Even as the party-list/highest-remainders system puts immense pressure on large parties to split up, the DAB has remained intact. Instead of a two-party pro-democracy/pro-Beijing split, Hong Kong has one dominant pro-Beijing party leading a handful of smaller ones opposing a splintered constellation of opposition parties.

A complicated election to a rigged legislature using a voting system designed to help well-organized establishment parties over more fractious pro-democracy forces: a democracy that even the Chinese Communist Party could love.