For Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor Bill Bolling and Florida’s former Governor Charlie Crist, Republicans who were blocked from higher office from within their own party, their political destiny hangs on a momentous decision in this winter of 2012: whether to sever their lifelong loyalties to the Republican Party. They need a mixture of two elements to succeed, only one of which they can control: opportunism and party realignment.

For Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor Bill Bolling and Florida’s former Governor Charlie Crist, Republicans who were blocked from higher office from within their own party, their political destiny hangs on a momentous decision in this winter of 2012: whether to sever their lifelong loyalties to the Republican Party. They need a mixture of two elements to succeed, only one of which they can control: opportunism and party realignment.

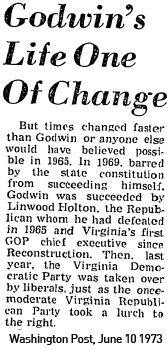

By default, party switchers appear spineless. Over time, party switchers have performed less well even if they are re-elected under their new party banner. However, if the voters and parties are rearranging themselves as fast as the politicians are, they are more forgiving. Thus the contrast between Mills Godwin, the only man to be elected Governor of Virginia as both a Democrat in 1965 and Republican in 1973 at a time when Virginia political parties were reshuffling, and the losers. Sen. Arlen Specter, Rep. Parker Griffith: two men who switched after being elected by their original parties at a time of political party stability, and were punished by their new party in primaries.

Of Bolling and Crist, Charlie Crist stands a much better chance of following in Godwin’s footsteps (in reverse), but the path is more difficult for both. There has been no similar massive change in the party coalitions in either Virginia or Florida in the last decade, making it harder for both of them to break the system open.

Bolling is rumored to be considering an independent bid for Virginia governor in 2013, and Crist has switched to the Democratic Party and is contemplating a return to Florida’s governorship in 2014.

Bolling is rumored to be considering an independent bid for Virginia governor in 2013, and Crist has switched to the Democratic Party and is contemplating a return to Florida’s governorship in 2014.

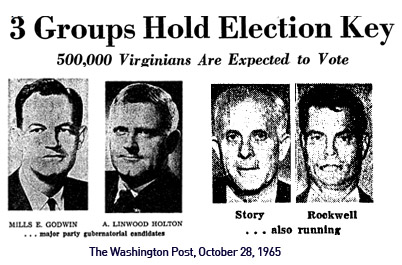

For both, Virginia’s chaotic three-way gubernatorial election of 1965 is a historical parable that, like most historical parables, is of debatable applicability but is undeniably fascinating. That year, Mills Godwin, a conservative Democrat, defeated Republican nominee Linwood Holton and segregationist splinter candidate William J. Story, who broke ranks from the Democratic Party. Godwin won decisively with 48%, to Holton’s 38% and Story’s 13%.

Crist, who was elected Governor previously as a Republican and is now out one term cannot escape at least a passing comparison to Godwin, who won the 1965 election as a Democrat, served his term, and was elected again as a Republican in 1973. For Bolling, the splintering of the conservative Byrd Organization in the 1965 election between Godwin and Story hangs as a ghost over any Independent bid that would split the conservative Republican Party between Bolling and Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli. This is not to say that either Bolling or Cuccinelli are segregationist, nothing could be further from the truth: the point is that intra-conservative fighting spilling over into independent challenges is nothing new in Virginia.

Throughout the mid 20th century, Virginia was dominated by a conservative, white Democratic machine led by Senator Harry Byrd: the fabled and feared Byrd Organization that owned state offices but remained silent on presidential races. In 1965, Mills Godwin was elected its last governor as a Democrat.

Throughout the mid 20th century, Virginia was dominated by a conservative, white Democratic machine led by Senator Harry Byrd: the fabled and feared Byrd Organization that owned state offices but remained silent on presidential races. In 1965, Mills Godwin was elected its last governor as a Democrat.

An ardent segregationist who believed in Massive Resistance, he switched sides ahead of the 1964 Presidential election, supporting Lyndon Johnson. 1964 was the first election without a poll tax, and black and poor white voters gave Johnson Virginia’s 12 electoral votes, the only Democrat to carry the Commonwealth between Truman ’48 and Obama ’08. Barry Goldwater’s extreme, anti-civil rights stances sent the African-American vote running from the party of Lincoln to the party of Johnson, and Godwin worked hard to court their vote.

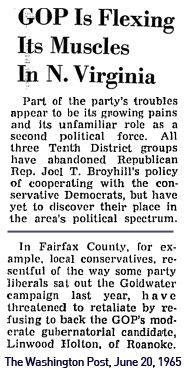

The Goldwater backlash was not limited to African-Americans. Virginia Republicans nominated Linwood Holton, a moderate from Roanoke, to hopefully make a good showing against Godwin.

The Goldwater backlash was not limited to African-Americans. Virginia Republicans nominated Linwood Holton, a moderate from Roanoke, to hopefully make a good showing against Godwin.

The unraveling of the Byrd Organization gave the Republican Party a chance to be a real second party for the first time in decades. Their tacit agreement to support Byrd Democrats (as profiled to the right in a 1965 Washington Post clip) was giving way to the chance that one of their own might win, but the Goldwater candidacy had alienated many moderates within the Republican Party. This intra-conservative squabbling led to less support for Holton and chaos on the right.

Party switching is far more common in fluid parliamentary systems that use proportional representation than America’s first-past-the-post approach that causes a rigid two-party structure to be the norm. In such a system, it takes extraordinary forces to cause politicians to switch parties, and even greater extraordinary forces for apostates to succeed afterwards: but for some, it is the only way forward. It takes some principled opportunism, a crass mixture of severing lifelong loyalties, poisoning friendships, raw ambition, and fervent belief in one’s own destiny and the correctness of their principles: this is the element the party switcher can control.

What the switcher can’t control is the second element, party realignment. The parties must change around the politician just as much as the politician changes himself. It takes seismic, cataclysmic shifts to pulverize the bedrock bases of both parties and recast this amalgam and debris into two new parties. Party switchers and leavers will frequently assert that they didn’t leave the party, the party left them: but whether this is true is not up to them.

So what does that say for Crist and Bolling? Both men certainly have the first part, no man who wasn’t filled with ambition would even contemplate such a move. The environment of 1965, with national partisans and state partisans in conflict, and state partisans in mortal combat with themselves, was a chaotic era of party realignment that lent itself well to ambitious party switchers. What voter could punish for disloyalty when he himself was redefining his partisanship? Regardless, 1965 was the end of the line for the Byrd Organization. Virginia has a one-term limit for its governors, and in 1969, Mills Godwin was succeeded by Linwood Holton, the man he defeated, the first Republican governor of Virginia since Reconstruction.

For Bolling’s gambit to succeed in a 3-way race, he would have to convince Virginia liberal Republicans to flee Cuccinelli like conservative Democrats fled Howell. But this pretends that there are any liberal Republicans left in Virginia, and also requires that the ideological changes in the Democratic and Republican parties were as tumultuous as they were in the late 60s and early 70s. Bolling can’t simply join the Democratic Party and try to make it a two-way race because both parties are largely the same as they were in 2005 when Bolling was elected Lieutenant Governor. No major seismic shift has happened, and Democrats would never let him past a primary.

One faction missing from the 1965 election were the populist liberals, who were corralled into Godwin’s corner. The Goldwater implosion of 1964 which pummeled Virginia Republicans was followed by the McGovern debacle of 1972 which shattered Virginia Democrats. Howlin’ Henry Howell, who once opined that “a liberal in Virginia is someone who believes in life after death”, was a fiery opponent of the fiscally tightfisted, socially reactionary Byrd Organization. Charging at the dying Organization from the left, he lost the 1969 Democratic primary for Governor, but after the death of Lieutenant Governor J. Sargent Reynolds in 1971, was elected Lieutenant Governor and seized the Democratic nod in 1973.

One faction missing from the 1965 election were the populist liberals, who were corralled into Godwin’s corner. The Goldwater implosion of 1964 which pummeled Virginia Republicans was followed by the McGovern debacle of 1972 which shattered Virginia Democrats. Howlin’ Henry Howell, who once opined that “a liberal in Virginia is someone who believes in life after death”, was a fiery opponent of the fiscally tightfisted, socially reactionary Byrd Organization. Charging at the dying Organization from the left, he lost the 1969 Democratic primary for Governor, but after the death of Lieutenant Governor J. Sargent Reynolds in 1971, was elected Lieutenant Governor and seized the Democratic nod in 1973.

Howell and Scott are about as far away from each other ideologically as one could be, but they shared a fair distance from the center. Conservative Democrats, horrified by the McGovern nomination in 1972 and equally as appalled by Howell’s nomination in 1973, began bolting to the Republican Party and convinced Godwin to return as Republican nominee in 1973. Godwin was nominated without opposition at the 1973 Republican Convention: a party switcher who faced nary a primary challenger! Such was the power of realignment and a well-known name. In November, Godwin won 51-49 in one of the closest gubernatorial elections in Virginia history.

Bolling can’t walk into Democratic arms like Godwin walked into Republican arms, so he’s left with this quixotic independent option. If Bolling entered the Democratic primary for 2013, he’d be laughed out of the ballot box, a marked contrast to the 1973 Republicans. While it worked for candidates like Lincoln Chafee, elected Senator for Rhode Island as a Republican, defeated, and then elected as an independent for Governor, Bolling is no Chafee (or Angus King). Bill Bolling has been lieutenant governor for nearly eight years, and most Virginians can’t pick him out of a lineup or think of a single thing he’s done. Chafee and King were institutions.

For Crist, however, his chances depend on a primary. Can he really count on Florida Republicans changing their minds about Scott like conservative Democrats decried Howell? Most likely not. He already tried running an independent in a three-way race and lost big in 2010 to Marco Rubio. Democratic nominee Kendrick Meek captured the black vote, leaving Crist fighting for the remaining part of the Democratic coalition and whatever scraps of the rest of the electorate he could.

Knowing that no matter what happens, the black vote would remain straight-ticket Democratic, he knew his only option was to run as full-blown Democrat. Unfortunately for him, there has been no influx of disgruntled Republicans disgusted with Rick Scott that will take over the 2014 Florida Democratic Primary for him. Many of the Democratic primary voters who vigorously opposed him in past elections are still there, and may not be persuaded to change their minds.

Like Bolling, Crist will not walk into the Democratic field easily. If there has been any realignment at all, it’s been in the opposite direction Crist would want it to be: conservative Democrats, especially in the Panhandle, dying off or converting to Republican, leaving a more liberal, more partisan primary electorate in its wake. Even worse for Crist, Florida is a closed primary state. However, as someone with much higher name recognition who has spent over two years working on his Democratic bona fides, he stands a higher chance of being perceived as a sincere party switcher. Absent a cataclysmic party realignment though, he’s asking the same group of people that repeatedly tried to end his career to embrace him. This was a death blow for Arlen Specter, a Republican-turned-Democrat who was defeated in a primary by a partisan, registered Democratic electorate in 2010.

The stability and continued entrenchment of the current party system works against both Crist and Bolling. Mills Godwin and many other successful party switchers like Sen. Richard Shelby of Alabama avoided primary challengers from their adopted parties because the primary electorates changed as fast as they did. For Bolling, I don’t see any real options for him. He can’t win a Democratic primary. He can’t run as an Independent and win. What’s left for him?

For Crist, though, he has a way to survive a hostile, closed primary. Sure, the Democratic primary electorate is not radically different from the Democratic primary electorates that salivated at the chance to kick him out of office. What he needs is an empty bench of potential primary challengers: and in that respect, as of now, he’s quite lucky. But there’s still a long ways to go.